“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

—Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927), H. P. Lovecraft

There is nothing more terrifying to me than the sudden realization that I am, inescapably, out of my depth. It is the keen awareness, the visceral experience, of the unknown that brings on the bitter and metallic jolt of adrenaline. As I stood sweating in that apartment, watching friends perform the script I had written, I had no idea what I had gotten myself into. I had a consumer-grade Digital8 camcorder, a naked and blazingly white G.E. Reveal bulb in a ceiling fixture, and a homemade bounce board to add some fill light to each shot. The most sophisticated piece of equipment on that set was a two-hundred-dollar Azden two-stage shotgun microphone that was rigged up to an aluminum painter’s pole we were using as a boom. It was June of 2002, and we were shooting my first feature.

One Night on Oswald’s Green is about three adults who regularly get together to play a table-top role-playing game based on the fiction of the American horror writer Howard Philips Lovecraft (1890–1937). The group is somewhat dysfunctional – especially because they are not dealing well with the recent death of a long-time member in a freak accident. This provides the frame for the film-within-a-film, the story of the game scenario. In that scenario, the three players take the roles of late-1920s investigators, who travel to a remote New England town to look into strange events related to a reclusive scientist.

I had grown up deeply involved with role-playing games like this one, and my brilliant plan was to use the intricately painted miniatures that often serve as accessories for these games, along with detailed scale-model sets, to photograph the various tableaux of the game scenario with a digital still camera. My actors would provide the voice-over dialogue for their investigators, I would buy high-quality sound effects to layer onto the soundtrack, and some creative use of postproduction image panning would provide the visual movement that the metal miniatures could not.

Of course, it all fell apart. Like so many before me, I had naïvely embarked upon the complicated undertaking of making a movie with almost no money at all. I had a camera and creativity and friends, and I thought my problem-solving skills would be enough to overcome the challenges that would eventually come my way. Once my tiny crew and I wrapped principal photography, I spent the rest of the summer recovering from that frenzied, two-week production schedule, the realization that I didn’t have the resources to finish the film slowly sinking in. My own skills weren’t up to the task of turning my visions into apparent reality; I had already painted the miniature figures, but building the intricate model sets was beyond my ability, and my graduate student stipend was not equal to the task of hiring people who might be able to do it. It was stomach-wrenching to think of all the time and effort my friends had put into this project, and I couldn’t bear to think about the moment when I would have to confess that I had simply bitten off more than I could chew. None of us would ever see this film, and certainly none of us would ever premiere it at the annual H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival (HPLFF).

All of these worries and doubts were pushed aside, however, when I was called up to active duty. In a previous life, I had been in the army, and now they wanted me back for twelve more months. I thought very little about the film that year. The tapes, the equipment, my computer, and all the miniatures sat in storage, waiting for my return. It was a loose end, like my graduate studies, and the thought of it made me ache.

So I tried my best not to think about it. Still, it is sometimes hard to keep our interests a secret. Over the course of my tour of duty, my boss, Chief Warrant Officer Marler, and I talked a lot about books and movies. Eventually, I got around to mentioning Lovecraft, and we discovered that this was perhaps the one thing we had in common outside of the uniform, the one thing that switched off our automatic defense mechanisms (mine sullen, his surly). When my year was up, the Chief bought me the two volumes of the Annotated Lovecraft as a going-away gift.

Lovecraft was an early-twentieth-century writer from Providence, Rhode Island, where he spent most of his life. From his youth he was fascinated by science and literature, especially the gripping short stories of Edgar Allan Poe and the fantastic mindscapes of Lord Dunsany. Eventually, Lovecraft combined these interests into his own particular species of weird fiction.

Lovecraft’s fiction falls into two broad categories: horror and dreams. Early on, he lamented that he wrote derivative “Poe stories” and “Dunsany stories,” and for some time he despaired of ever writing a true “Lovecraft story.” Though the quality of his output was tremendously varied over his short life – and there is a compelling case that his gargantuan correspondence deserves as much if not more attention than his fiction – he is now best known for a group of stories that the French author and filmmaker Michel Houellebecq terms “the Great Texts.”

These short stories and a handful of somewhat longer works, about a dozen in all, include “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Dunwich Horror,” “The Whisperer in Darkness,” “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” and “At the Mountains of Madness,” among others. Lovecraft set these stories in his modern day, though most of them take place in a curious geography of fictional New England towns like Arkham (with its ivy-covered Miskatonic University) and Innsmouth. His characters set out from such places in search of things that would have been better left unknown.

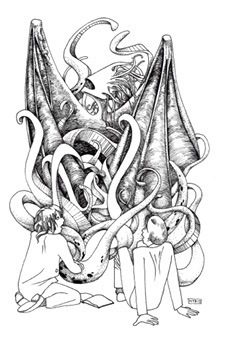

Most of this forbidden knowledge touches on a shadowy pantheon of extra-terrestrial and extra-dimensional beings with names like Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, Azathoth, and Yog-Sothoth. These entities are worshipped by nameless human cults as though they were malevolent gods. They are, in fact, supremely indifferent to humanity and our mundane concerns. The threat inherent in these tales of horror is not that these creatures are bent on our destruction; the extinction of the human species is usually posited as simply an inevitable by-product of their ascension. Often Lovecraft’s characters learn about these beings from books of forgotten and dangerous lore, the most famous of which is the Necronomicon, a fictional tome arguably more famous than the man who conceived it. Usually, these searchers are rewarded for their efforts with insanity or death (or both, in that order).

Most of this forbidden knowledge touches on a shadowy pantheon of extra-terrestrial and extra-dimensional beings with names like Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, Azathoth, and Yog-Sothoth. These entities are worshipped by nameless human cults as though they were malevolent gods. They are, in fact, supremely indifferent to humanity and our mundane concerns. The threat inherent in these tales of horror is not that these creatures are bent on our destruction; the extinction of the human species is usually posited as simply an inevitable by-product of their ascension. Often Lovecraft’s characters learn about these beings from books of forgotten and dangerous lore, the most famous of which is the Necronomicon, a fictional tome arguably more famous than the man who conceived it. Usually, these searchers are rewarded for their efforts with insanity or death (or both, in that order).

On my way home, I dove into those books and started thinking again about Oswald’s Green. None of the problems had gone away, but I started thinking about how I might return to it. The immediate path I chose was to attend the Lovecraft Film Festival in early October of 2003. Though I had never been, I had found it online a couple years before. I had ordered a handful of the festival’s best films off the internet in a VHS series called The Lurker in the Lobby. I saw Bryan Moore’s Cool Air (1999), starring a wonderful Jack Donner, and realized that there were indie filmmakers out there who could put together enough of a budget to make a satisfying period adaptation of a Lovecraft tale. I saw shorter films by Aaron Vanek like The Outsider (1994) and Return to Innsmouth (1999), as well as Bob Fugger’s From Beyond (1999). It was the discovery of this festival and these films that inspired me to want to write and produce my own Lovecraftian film in the first place.

Going to the festival was clearly, then, about returning to a time prior to my experiences over the past year. I also planned on seeing a number of old friends along the way, people I knew from my first active-duty stint in the 1990s as well as college friends from before that. I imagined it as a classic cross-country road trip of the kind I had always wanted to take. I would be driving alone, taking my time, camping to keep costs down. Here was nostalgia for a dream. I had taken many long trips by car, but none of them had ever seemed romantic enough to fulfill this desire I had, a desire that came to me fully formed via books and movies, a desire that smelled like diner coffee and pine forests and gasoline. And in the middle of it, there would be three days of Lovecraft adaptations. Jack Kerouac with tentacles.

Days of driving, my silver Ford skimming along hundreds of miles of asphalt, gave me a lot of time to think about what I had done, what I was doing, what I was going to see at the festival. None of that really prepared me for what I did see when I got there. At the time, the festival ran annually in the historic Hollywood Theatre in Portland, Oregon. (Now, the festival also has a separate run in Los Angeles.)

This art movie house, with its baroque façade, had been built in 1926 as a grand, 1,500-seat theater with a balcony, an orchestra pit, and an organ for silent film accompaniment. Over its long life, the grand theater had been chopped up into three smaller venues; the main floor was intact, but the balcony had been split into two screening rooms. The entire house was a bit threadbare, its eighty years showing in the stained carpeting and the cracked plaster.

What struck me most forcefully, though, as I entered the theater, was how it was so obviously filled with love: of film, of the building itself, of fans, of Lovecraft. Everyone I saw and everyone I met were all at the HPLFF for the same thing. The festival programmed a handful of features, many of which were examples of the lower-budget Hollywood films inspired by or adapted from Lovecraft like Beyond Re-Animator (2003) and Necronomicon (1993). There was also Ivan Zuccon’s Italian adaptation The Shunned House (2003) and a feature-length documentary The Eldritch Influence (2003). However, the bulk of the festival screenings were made up of independent short films, fan films essentially, like the ones I had seen in The Lurker in the Lobby. These are the films that most everyone really comes to see. The audience is filled with the filmmakers, and many of the filmmakers began as members of the audience.

The fan camaraderie was unlike anything I had experienced before, even in the military. Even though the days of driving had left me with a noticeable limp (I used my umbrella as a makeshift cane while I walked off whatever those bucket seats had done to me), I still sat happily and watched hours of short- and feature-length films. I hobbled around the dealers’ room filled with books and movies and memorabilia and resin sculptures and fans, everywhere fans. All sorts of people came: men and women, teenagers and seniors. Some looked very much like the fans you would find at any convention dedicated to some byway of popular culture. They tend to be male, between the ages of sixteen and forty-five, wearing tennis shoes and black T-shirts (preferably with some otherwise obscure Lovecraftian reference). But the Lovecraft set also attracts a strong contingent of the goth-punk crowd. They are onboard with the black, but they prefer leather, corsets, tattoos, and lots and lots of metal on their clothing and in their bodies. Mixed in among these are the notables: the filmmakers, authors, artists, and other movers and shakers that keep the festival train running with their output. These few are often dressed more formally, though the fabrics are still quite dark, with room for the occasional merlot necktie or ceremonial cloak Mixed in with all of these are not a few local Portlanders, who sometimes seem a little lost in the Hollywood Theatre, but who more often seem game for this annual carnival.

At the Pagan Publishing table, I flipped through books and supplements for Delta Green, a modern-day setting for the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game. In Delta Green, a super-secret U.S. government organization tries to protect the world from the mind-rending horrors of the Cthulhu mythos. Sitting behind the table was Adam Scott Glancy, who somehow bears an uncanny resemblance to Walter Sobchak in The Big Lebowski without really reminding you of John Goodman. Turning from the Pagan Publishing table, I met and chatted with Jack Donner, who had a table all to himself where he was talking with attendees and signing eight-by-ten glossies. Donner has been acting for over half a century and is well known to another group of fans as Romulan Subcommander Tal from the original Star Trek television series, though his roles have spanned across many genres on stage as well as on large and small screens. He is the kind of tall that remains tall even when seated, and his shock of white hair, hollowed cheeks, and closely trimmed moustache and goatee confirm rather than lend his air of dignity.

I recall very little of what we said, but I remember his voice, deep and resonant, perfectly in keeping with his presence. Other festival attendees would step up to the table, say hello, maybe compliment Donner on his work in Star Trek, but almost all of them, myself included, praised his performance in Bryan Moore’s Cool Air. His portrayal of Lovecraft’s character, Dr. Muñoz, who must remain in his freezing apartment in order to survive, is one of the most frightening of the entire Lovecraftian film library and all the more so because it is so touching. He had embodied the mad scientist filled with regret, and here we all were smiling with him and shaking his hand.

When a couple people I had been talking to announced that they were going over to the nearby Moon and Sixpence Pub, I went along. It was there, over pints, that I met some of the festival’s more active filmmakers. I spent the most time speaking with Aaron Vanek, a young filmmaker in L.A., who was already responsible for several indie Lovecraft films. His last film was The Yellow Sign, a slight departure from orthodox Lovecraftian filmmaking, as it is an adaptation of Robert Chamber’s tale of cosmic horror. Though I had never met Aaron before, I had seen him in a behind-the-scenes featurette from one of his films. When Aaron found out that I had driven across the country to get to the festival (most attendees live on the West Coast), I was welcomed as an honorary “Lurker” on the spot. From that point on, I felt like I was part of the festival: not just a tourist in the land of Lovecraft, but a citizen.

Much of this feeling came from the fact that the organizers not only welcomed me, but also asked me to help. After the screening of The Shunned House, the festival hosted a Q&A with Ivan Zuccon, the director. Ivan speaks English, but he is somewhat hard of hearing, so they needed someone to stand on stage with him and relay the audience’s questions so that he could answer. As I stood on the stage, listening to Ivan and the audience, I felt like I was contributing to their enjoyment of the festival. That wound up being the defining moment for me. It wasn’t just the films that made the festival experience what it was; it was the people and their exchanges of greetings, memories, art, ideas, and enthusiasm.

My experience at the festival did not provide a revelation about how I could salvage One Night on Oswald’s Green, but it did provide the kernel of something else. Years later, I would write a screenplay that fictionalizes that first road trip to the HPLFF and turns it into a Lovecraftian journey into madness called Cult Flick.

I didn’t write it so that I could produce it in the way that I had One Night on Oswald’s Green. In fact, I did not expect that anyone would produce it. Cult Flick is not a commercial script.

It is a niche artifact, a script with which a relatively small number of readers would connect. However, I did know that the HPLFF was stuffed to the gills with those readers. Here was a home for what I had to say; here was the cult. I entered the script into the festival’s screenplay competition in 2010, and by late summer I received word that Cult Flick was among the six finalists. I would be returning to Portland seven years after my initial visit, and this time I would be going as a guest of the festival.

Each year since my initial visit to HPLFF, the submissions have gotten better. There are still some howlers, some unintentionally horrifying, some unintentionally humorous. Typical of these is the short video “At the Reefers of Madness” by Brian Clement, in which a group of Miskatonic University stoners summon Nyarlathotep through a dimensional rift in their linen closet and demand that he provide them unlimited weed. The Dark One obliges them in exchange for certain…sacrifices on their part. The admittedly catchy tag line for the film admonishes, “It’s a dimensional gateway drug.” But the heights get higher with each festival run, as more and more filmmakers bring their talents and inspiration to bear on the considerable challenge of adapting Lovecraft’s weird fiction to the screen.

The standout examples of this quality output are two longer films produced by a group known as the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society (HPLHS): Call of Cthulhu (2005) and The Whisperer in Darkness (2011). Both of these films attempt faithful adaptations of Lovecraft short stories essentially by imagining what a contemporary cinema adaptation might have been like. Lovecraft wrote the short story “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1926, though it did not appear in print until 1928. Accordingly, the HPLHSfilm of the same name is produced as a black and white silent film, complete with dialogue intertitles and the kind of musical score that would have been played by the house orchestra in a movie palace of the time. It tells the story of Francis Wayland Thurston, who pieces together a mystery left behind in a box of documents by his granduncle, Professor George Gammell Angell of Brown University. Prof. Angell collected various documentary accounts of strange dreams, earthquakes, dark rituals, and archaeological discoveries all over the globe that hinted at the truth of certain unspeakable legends concerning The Great Cthulhu.

Cthulhu, an extra-terrestrial being of immense power, has been slumbering beneath the ocean in his sunken city of R’lyeh “until the stars are right,” when he will rise and end the world as we know it. The film relates Thurston’s investigation of Angell’s work as a silent film, complete with a wild cult ritual in the Louisiana bayou, a visit to the newly risen city of R’lyeh by a crew of Norwegian sailors, and a final climactic encounter with a terrifying stop-motion Cthulhu. For Lovecraft fans, this film came as a breathtaking revelation.

The HPLHS immediately set to work on their next feature, The Whisperer in Darkness. This story first appeared in Weird Tales in 1931, and so the film is figured as a proto-film-noir, science-fiction thriller in black and white with synchronized sound. In it, Albert Wilmarth, a professor of literature at Miskatonic University, addresses local concerns about strange creatures that have been found dead in the aftermath of severe flooding in the Northeast. Wilmarth is interested in folklore, but he doesn’t believe that the rural Vermont folk are actually finding strange beings. However, when one of those locals presents him with shockingly strange photographic evidence, he feels compelled to investigate further.

His journey to the wilds of Vermont brings him into contact with a chilling conspiracy between humans and fungoid extra-terrestrials known as the Mi-Go, creatures who possess the technology to remove the human brain without ceasing its function and place it in a specially designed cylinder, ostensibly for the purpose of space travel (since the human body cannot withstand the rigors of the experience). The short story ends here with Wilmarth running in horror from his discovery, but the film continues and plays out a further scenario in which the conspiracy’s true purpose is not alien abduction but alien invasion.

The film faithfully presents Lovecraft’s story as though it were released as one of Universal’s horror classics and then cranks up the horror even further by adding a diabolical alien laboratory in a cave, a dramatic summoning ceremony crawling with CGI Mi-Go that look like huge insects, and a thrilling aerial chase between a biplane and the hideous Mi-Go. After Call of Cthulhu, I was not certain that the HPLHS could top themselves, but they did. And now I can’t wait for more.

Both Call of Cthulhu and The Whisperer in Darkness engage in nostalgia for a lost cinema culture. Every frame of these films attempts to evoke a movie experience from the early years of the classical Hollywood studio era. From the titles to the makeup to the props to the special effects, there is little beyond the sharp-edged digital video image quality to jar the viewer out of the illusion that the films are lost titles from the Universal Studios vault. But that feeling of having succeeded in traveling back in time (aesthetically at the very least) is not, I think, the point of these films. They are adaptations, after all, and every adaptation is on one level nostalgic: it is trying to transform a narrative from one medium into another in order to recapture (and possibly even enhance) whatever value the audience took away from its experience with the source. We cannot ignore the fact that most cinematic adaptations are also mercenary adaptations; the transformation comes at a price. The formula in this case is assumed to be that audiences will line up to pay money in order to recapture that value from the past.

Both Call of Cthulhu and The Whisperer in Darkness engage in nostalgia for a lost cinema culture. Every frame of these films attempts to evoke a movie experience from the early years of the classical Hollywood studio era. From the titles to the makeup to the props to the special effects, there is little beyond the sharp-edged digital video image quality to jar the viewer out of the illusion that the films are lost titles from the Universal Studios vault. But that feeling of having succeeded in traveling back in time (aesthetically at the very least) is not, I think, the point of these films. They are adaptations, after all, and every adaptation is on one level nostalgic: it is trying to transform a narrative from one medium into another in order to recapture (and possibly even enhance) whatever value the audience took away from its experience with the source. We cannot ignore the fact that most cinematic adaptations are also mercenary adaptations; the transformation comes at a price. The formula in this case is assumed to be that audiences will line up to pay money in order to recapture that value from the past.

But I also cannot help thinking that the act of nostalgia is not simply a turning back. It is not only an attempt to refuse the present by returning to the past. It is not merely a surrender to the fear that ingenuity and originality are no longer. Instead, nostalgia is a kind of cultural work that inevitably reworks. In the same way that an adaptation can never be completely faithful to the original – there is no way to step into that same river twice – so too is it impossible to actually return to that earlier, happier time. The mode of nostalgia will never deliver someone to that earlier, better place, but it will deliver them somewhere. Nostalgia, then, can be one of many strategies for responding to a frustrating present.

Lovecraft himself found much of his world frustrating while he was alive, and he felt immense nostalgia for periods of history he never experienced directly, in particular the eighteenth century. A number of critics have noted that one of the main reasons Lovecraft’s fiction has not been better regarded has less to do with his choice of genre and more to do with his writing style, which deliberately recalls eighteenth-century prose. One of his earliest extant stories, “The Beast in the Cave” (written 1905, published 1918), displays what some might call the worst excesses of this florid and archaic style. Consider the opening of this tale:

The horrible conclusion which had been gradually obtruding itself upon my confused and reluctant mind was now an awful certainty. I was lost, completely, hopelessly lost in the vast and labyrinthine recesses of the Mammoth Cave. Turn as I might, in no direction could my straining vision seize on any object capable of serving as a guidepost to set me on the outward path. That nevermore should I behold the blessed light of day, or scan the pleasant hills and dales of the beautiful world outside, my reason could no longer entertain the slightest unbelief. Hope had departed. Yet, indoctrinated as I was by a life of philosophical study, I derived no small measure of satisfaction from my unimpassioned demeanour; for although I had frequently read of the wild frenzies into which were thrown the victims of similar situations, I experienced none of these, but stood quiet as soon as I clearly realised the loss of my bearings.

This is not the writing of a Modernist author in tune with the literary avant-garde of his day. The style comes directly from the Gothic and sensation fiction published over a century before in England and the United States. The archaic syntax, evident borrowings from Poe (“nevermore”), and the preference for British spelling conventions would all count against him with mainstream critics. But for Lovecraft, this was no mistake. Though he had a cutting edge interest in science, he had no interest in the literary experiments of James Joyce.

And though his stories often harken back to earlier periods in American and European history for their background and style, they just as often reach back even further to a time on Earth before the development of homo sapiens.Lovecraft’s horror is famously a cosmic horror; it recoils at the vastness of the universe and humanity’s insignificance within it. The development of his perspective was linked directly to early-twentieth-century developments in physics and astronomy and their influence on Lovecraft’s essentially materialist view of the world. I think that in many ways, the nostalgic style of Lovecraft’s prose enhances the effect of his philosophical refusal of a romantic or mystical view of the world.

This is the kind of rhetorical move that the very best of the Lovecraft film adaptations are also making. The HPLHS and other filmmakers producing Lovecraft adaptations are making the films that they and a relatively small audience want to see. They are not making films for an audience of millions. However, they are using a cinematic style that was specifically developed in the early years of movies to attract and entertain mass audiences in order to drive profits in a massive industry. It is the filmic equivalent of an archaic prose style with romantic associations. We need only look to the critical and popular success of The Artist (2011) to know that archaic film style is still effective film style and that audiences are indeed subject to those romantic associations. Hollywood has failed to provide them with satisfying Lovecraft adaptations, presumably because Hollywood producers do not feel that faithful adaptations of Lovecraft stories would be profitable at the box office.

Guillermo del Toro, who is a keen Lovecraft fan and an accomplished director of big-budget fantasy-horror films (the Hellboy films and Pan’s Labyrinth among them) had to shelve his plans for a big-budget adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness after pre-production was well underway. Fans had known for years that del Toro wanted to do the film and, in general, their faith in his ability to do the story justice was high. But last year del Toro reported that the studio backers had become squeamish about the film’s price tag and pulled the plug. They were worried that such an expensive Lovecraft adaptation wouldn’t find the audience it needed to be profitable.

If updated adaptations of Lovecraft stories fail to connect with fans in a satisfying or inspiring way – in some way that will approximate the emotional responses they had to the original story – then one might be forgiven for believing that the stories are simply not readily adaptable. However, another response is not to try to bring the stories with us, but rather to set out on a quest to return to the story in its original context, to get outside of our time, our modes, and ourselves. The HPLHSexpends enormous amounts of time, energy, and cash imagining what it would have been like to make a movie out of a Lovecraft short story in 1928 or 1933. Simultaneously, they create films that encourage us to think not only about how we perceive movies and our relationship to them, but also about the way that we conceive of the stories we tell ourselves. Instead of continuing with the fiction of the moment, these filmmakers explicitly gesture to the fiction of the past, and as a result they illuminate the present moment in ways that might allow us to better understand ourselves.

It is difficult to dismiss the potential relevance of the waning of celluloid film at this point in motion picture history. The HPLHS would be the first to admit that the digital revolution makes their adaptations possible. Producing their movies on celluloid, whether 35mm or the more indie-friendly 16mm, would simply be cost prohibitive. Even Hollywood producers are finding this to be the case. Kodak has eliminated its film department and filed for bankruptcy, while the manufacturers of 35mm motion picture cameras have quietly ceased production. More and more theaters are switching out their 35mm projectors for digital equipment. Perhaps most importantly, cineplex audiences are less and less capable of – and maybe less and less interested in – telling the difference between high-definition digital video and celluloid film. We are not witnessing the end of film in an absolute sense, but we are certainly witnessing the end of celluloid film as the medium of choice for the motion picture industry.

It took a quarter century for Hollywood to recover from the transition to sound film before it was ready to produce films like Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), but that transition was much more fundamental than our current one. The addition of synchronized sound and the more gradual addition of the three-color Technicolor process were seminal moments in the development of commercial motion pictures. It seems to me that the transition from celluloid to high-definition digital video is not of the same order; the whole point of this transition seems to be a preservation of aesthetic standards rather than a revolution in them – Hollywood wants you to believe that HD is just as good as film, not better and not different. One could argue that 3D technology has the potential to revolutionize cinema in the way that sound and color did, but if that’s the case, then filmmakers have not discovered the secret formula that will get audiences to recognize that the revolution is upon them.

All the same, the end of commercial celluloid has spurred the production, release, and success of films like Hugo (2011) and The Artist, both of which are deeply nostalgic for the days of silent film. What are these films trying to do at this moment in cinema history when we are about to leave celluloid film behind? Are they trying to go back and touch upon what we have come to see as some of the stylistic high points in film history in order to take stock of what we should take with us into the future? Are they saying something about the inadvisability of striding boldly into that future?

The answers to the latter two questions are “no” on both counts. Though these films tend to look back fondly on the early days of celluloid cinema, neither of them posits anything essential about those days. Indeed, Hugo (itself an adaptation of a graphic novel) partakes freely and gleefully of the latest in 3D technology while seeming to look back, and The Artist needs to use CGI artists in order to recreate the Hollywood(land) of the late 1920s. Hugo uses new techniques to talk about old technology, while The Artist uses recent technology to remind us that old techniques still work.

The answers to the latter two questions are “no” on both counts. Though these films tend to look back fondly on the early days of celluloid cinema, neither of them posits anything essential about those days. Indeed, Hugo (itself an adaptation of a graphic novel) partakes freely and gleefully of the latest in 3D technology while seeming to look back, and The Artist needs to use CGI artists in order to recreate the Hollywood(land) of the late 1920s. Hugo uses new techniques to talk about old technology, while The Artist uses recent technology to remind us that old techniques still work.

The HPLHS calls their particular mix of old and new cinema techniques “Mythoscope.” For them, the availability of professional-consumer versions of commercial high-definition technologies means that they can conceive, design, and produce highly faithful motion picture adaptations of the Cthulhu mythos stories without waiting for studio number crunchers to decide whether the opening weekend box office would be sufficient to justify the financial risk of production. The HPLHS takes on that risk because they are more interested in the finished film than they are in its bottom line. They are their own biggest fans.

They are not actually going back to a happier time, because in that time, Hollywood was not making the films that they would one day want to see (or at least Hollywood wasn’t making all of the films they would want to see). More importantly, Hollywood still isn’t making what they want to see. The HPLHS is in some sense correcting the history of cinema by providing the contemporary adaptations of Lovecraft’s works that were not created at the time and that are still not being created.

The HPLHS, and all the indie filmmakers at the Lovecraft Film Festival – and thousands of other indie filmmakers at other film festivals around the world – are shouting their slogans at the barricades of the digital revolution, saying, “This I what I want to see and hear. This is what I want to know. And if you won’t show it to me, I will create it myself.”

Lovecraft began his writing career with the archaic and derivative style on display in the opening of “The Beast in the Cave.” Many years later, though, as he found the words that would best convey the horrors he had in store for his readers, his art grew more powerful and assured. The first few lines of “The Colour out of Space” (1927) are representative of this mature talent:

West of Arkham the hills rise wild, and there are valleys with deep woods that no axe has ever cut. There are dark narrow glens where the trees slope fantastically, and where thin brooklets trickle without ever having caught the glint of sunlight. On the gentler slopes there are farms, ancient and rocky, with squat, moss-coated cottages brooding eternally over old New England secrets in the lee of great ledges; but these are all vacant now, the wide chimneys crumbling and the shingled sides bulging perilously beneath low gambrel roofs.

The scene remains atmospheric in the best traditions of weird fiction, but the writing is no longer drenched in the purple ichor of Gothic prose. Lovecraft needed to begin in that cave. He needed to go back and plumb the depths of the literature he knew and loved best in order to discover his own way forward. I think the efforts of the HPLHS are doing something very similar today. They are reaching back into our cinematic past to find something that never was but perhaps should have been.

Brian R. Hauser is an assistant professor of humanities & social sciences at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York. His feature-length screenplay Cult Flick won the 2010 H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival screenwriting competition. Hauser is also the writer and director of the film Nontraditional.

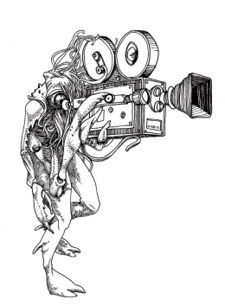

Harriet "Happy" Burbeckis a New Orleans comic artist, illustrator, and musician. She has shown her work at a number of galleries in the Crescent City, including Mimi’s in the Marigny, Du Mois Gallery, Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center, and The Candle Factory.